We have a new interesting publication from the group. We found that those adhering to the EAT-Lancet diet had decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. The association was independent of the genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes.

Take a look at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0026049523000045?via%3Dihub

Sugar-Coated: Let them eat cake?

My research interest over the past few years focused on increasing the amount of evidence exploring the link between sugar consumption and disease development (particularly cardiovascular disease) in the context of nutritional recommendations. Therefore, as part of my doctoral thesis, I have conducted four studies on sugar consumption, with different factors connected to disease development in a large sample of the adult Swedish population.

For years, many nutritional recommendations for sugar intake used the risk of causing micronutrient dilution as a basis for their advice. Micronutrient dilution is characterised by a decreased consumption of nutrient-dense foods (like fruits and vegetables) due to an increased consumption of energy-dense foods (like processed snacks and sodas), which are high in fats and sugars and low in vitamins and minerals. My first study confirmed that the higher the intake of added sugars in the participants, the more likely they were to have a low intake of vitamins and minerals. Found in two independent samples of Swedish adults, these results pointed towards the continued existence of micronutrient dilution for over two decades.

Cardiovascular disease remains one of the greatest causes of disease and mortality worldwide. Therefore, understanding the dietary risk factors for cardiovascular outcomes is important in order to establish nutritional recommendations. Many cardiovascular diseases evolve from a phenomenon called atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a process by which fatty materials accumulate on the walls of the arteries reducing their diameter, which decreases blood flow to organs. This accumulation can also form plaques that can dislodge and cause other pathologies.

My second study, investigated the association between several forms of sugar consumption and a marker of atherosclerosis called intima media thickness. This marker measures the thickness of the wall of the carotid arteries and can predict the possibility of developing cardiovascular diseases later on in life. However, this study could not find any conclusive link between sugar consumption and intima media thickness. While participants with a higher sugar consumption tended to have thicker artery walls, this finding would need to be studied further to confirm an association.

One of the most dangerous presentations of cardiovascular disease is stroke. Stroke is defined as a loss of brain function due to lack of sufficient blood flow. This lack of flow can occur if there is bleeding (haemorrhagic stroke) or if the blood vessels are blocked (ischaemic stroke). Stroke, like many other cardiovascular diseases, can be influenced by modifiable lifestyle factors, such as diet. My third study, analysed the risk of developing stroke within the context of dietary patterns considered healthy. Two healthy dietary patterns were chosen for such effect: following the Swedish dietary guidelines, and following a Mediterranean-style diet. In this study, a protective effect against stroke was found for individuals who better followed the recommendations of either of these healthy dietary patterns. For sugar in particular, a protective effect against stroke (particularly for ischaemic) was found in individuals consuming less than 200ml of soda per day, as recommended by the Mediterranean diet. Interestingly, a protective effect against stroke was also found for individuals consuming more than the three servings of sweets and pastries per week that the Mediterranean diet recommended. This contradictory finding could be explained by two possible scenarios. First, the deep-rooted Swedish tradition of fika (a break from activity where a hot beverage is consumed usually accompanied by a pastry). Fika breaks are not necessarily associated to an overall unhealthy diet or other unhealthy behaviours. Plus, the social element involved in this tradition has also proven to have beneficial health effects. Second, the fact that sugars in liquid form (like sodas) have a much more acute effect on our body than those consumed in solid form (like sweets and pastries).

Lately, scientists around the world have started to point towards the need for individualised advice when it comes to nutrition. As a result, the study of genetic markers in nutritional research has been on the rise to help understand the inherent differences between individuals. The first step towards understanding these disparities is to identify genetic variants that can be traced to the intake of specific foods or nutrients. In my fourth study, the association between genetic factors and sugar consumption was investigated. A connection was found between a genetic region in chromosome 19, linked to the fibroblast growth factor 21 gene, and the intake of sugar. This particular gene is known to code a hormone that has been previously linked to both intake and preference for sweet foods.

Informing nutritional recommendations on a regional, national, or international level is just the tip of the iceberg. Evidence-based dietary guidelines are usually the stepping stone for advising public health policies and strategies aiming to improve the health of millions. All in all, it seems that the study of sugar consumption still presents us more questions than answers. Solving our sugar-coated environment requires a multidisciplinary approach much more complex than what I could have covered during my time as a doctoral student. However, we should not stop wondering: should we have our cake, or should we eat it?

Although my doctoral thesis has been able to establish links between sugar consumption and both micronutrient dilution and genetic factors, the connection between sugar intake and more complex conditions, like cardiovascular disease, grants further study. While the overall scientific evidence is still inconclusive in its details, we should nonetheless aim to follow this simple advice: eat less sugar, you are sweet enough already.

Learn more!

I will be defending my PhD project “Sugar-Coated: the role of sugar intake and cardiovascular disease development in the context of nutritional recommendations” the next 21st of April 2022 at 13:30. This is a public defence seminar, so all are welcome! Join us at Agardhsalen, Clinical Research Centre (Jan Waldenströms gata 35), Malmö or on Zoom (Meeting ID: 628 4387 4127). You can also access the book and published papers here.

Presentation at the LUPOP methods seminar

Emily Sonestedt had a presentation on “Methodological considerations in nutritional epidemiology” at the LUPOP methods seminar on April 7th 2022.

Sugar-Coated: Living in a sugar-coated world

We are presently living in a sugar-coated environment. Nowadays, sugar is easily accessible, cheap, and present in up to three out of every four products that we can buy in supermarkets. As a result, the individual consumption of sugar worldwide has increased fifty-fold over the past 200 years. Just as sugar intake has increased, so has the concern about how it might impact our health. While the connection between overall diet and disease has been explored widely, there are still unanswered questions regarding sugar consumption specifically.

What is sugar?

We tend to interchangeably use the terms carbohydrates and sugar, but this is a common misconception. While all sugars are carbohydrates, not all carbohydrates are sugars. Sugar represents the simplest form of carbohydrates, consisting only of one or two molecules. They are soluble in water and are present (naturally or added) in foods and drinks granting them their sweet taste. However, sugars can also be used as part of other processes, such as preservation (like in jams) or fermentation (like in wine). Sugars are naturally present in fruits, vegetables, or milk; and are usually added to pastries, sweets, or sodas, among others.

Which sugars should we be worried about?

Dietary sugars are usually classified into total sugars, free sugars, and added sugars. Added sugars are those simple carbohydrates that are not naturally present in foods and beverages. These sugars have been, as the name indicates, added to foods during processing, manufacturing, cooking, or consumption. The definition of free sugars includes all added sugars plus sugars naturally present in honeys and syrups, as well as in fruit and vegetable juices and juice concentrates. Lastly, total sugars is a term used to refer to all sugars contained in the diet, whether they are added, free, or present in whole fruits and vegetables, or in dairy products.

Sugars consumed in either added or free form are generally considered more harmful for our health. Added sugars are not naturally present in foods and beverages so they only add to the caloric intake without any additional value. While the free sugars from, for instance, natural juices might still provide vitamins and minerals, these have less fibre and nutritional benefits than consuming the fruit whole.

Moreover, sugars that are consumed in liquid form present two additional issues. First, they do not make us feel as full, so we end up consuming more than we really need, adding to our overall caloric intake. Second, as they do not require digestion, they are more easily absorbed causing more acute effects in the body.

How much sugar should we eat?

Answering this question is more difficult than one might think. Even the scientists behind national nutritional recommendations (such as the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and Public Health England, to name a few) and international organisations (such as the World Health Organisation) have not managed to reach consensus. To this day, there is still a disagreement as to which type of sugar to focus on (added or free), where to set up the threshold for safe consumption, or which health outcomes to use as a basis for recommendations.

As a result, the European Food and Safety Authority set out to investigate sugar consumption in relation to pregnancy-related conditions, dental caries, and chronic metabolic disease, which include pathologies of the heart and the blood vessels (cardiovascular disease), diabetes, and obesity, among others. The European Food and Safety Authority concluded that while there is in fact an association between sugar consumption and the development of chronic metabolic diseases, there is not enough scientific evidence to establish a safe consumption threshold, particularly when related to cardiovascular disease. Nonetheless, their overall recommendation is to reduce our consumption of added and free sugars to a minimum within the limits of a nutritionally adequate diet.

Learn more!

I will be defending my PhD project “Sugar-Coated: the role of sugar intake and cardiovascular disease development in the context of nutritional recommendations” the next 21st of April 2022 at 13:30. This is a public defence seminar, so all are welcome! Join us at Agardhsalen, Clinical Research Centre (Jan Waldenströms gata 35), Malmö or on Zoom (Meeting ID: 628 4387 4127). You can also access the book and published papers here.

Food Systems Roadmap: From the 20th century Green Revolution to the 21st century Sustainability Goals

Dariush Mozaffarian, is a cardiologist and public health expert whose work at Tufts University (Boston, USA) focuses prominently on science-based food and nutrition policies aiming to tackle obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the US and globally. Dr. Mozaffarian, introduced us to how food systems should look in the 21st century to be able to tackle our current and future challenges, during the Transforming Food Systems session at the American Society for Nutrition (ASN) conference: Nutrition Live Online 2021.

Mapping sustainability for food systems

In the midst of the second year of the COVID crisis, we cannot deny that this is not the only pandemic we are dealing with nowadays. The current global dietary patterns pose a massive risk for developing chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. These dietary patterns are thus the source of many of the major causes for death and morbidity worldwide but they are also a key factor in sustainability.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), proposed by the United Nations in 2015 comprise 17 comprehensive goals set to be met by 2030. Unfortunately, many of these goals are not going to be achieved due to what is still NOT changing with our existing food systems. When it comes to the role of food and nutrition on these goals, the biggest focus is placed on ending hunger (SDG 2) and climate action (SDG 13). Indeed, lack of access to healthy and nutritious food is still a very serious issue in many parts of the world, and 25% of all climate emissions are due to the agricultural and food production sector. But we often forget that food and nutrition can have a direct impact on our overall health and well-being (SDG 3) and not enough focus is being placed on this, which is a “big missing link” as Dr. Mozaffarian called it, since “to think about food systems is really to think about chronic diseases”.

Additionally, food waste is also a problem not being sufficiently addressed in relation to responsible consumption and production (SDG 12) since our current food systems are contributing greatly to the loss of biodiversity and deforestation. This tendency for overproduction and overconsumption has also placed a great stress on our oceans, affecting the balance and ecosystems below water (SDG 14), which in turn might also affect our access to clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) because most of our water is being used towards agriculture. Food-related businesses have been the most direct way out of poverty (SDG 1) for many communities, whether this is on the production, distribution, or hospitality sectors, which is also an important sector when we want to guarantee a reduction in inequalities and disparities (SDG 10).

So, in order to have more sustainable agricultural practices and food systems we also need to think creating new routes in terms of innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), one of the biggest challenges for the future will rely heavily in the reinvention of industries to produce food that is both nutritious, sustainable and profitable.

As we can see, food and nutrition are very closely intertwined with many of the 17 SDGs. Thus, in order to design the food systems of the future we cannot keep thinking of food as an isolated item. We need to create food-related policies that consider all the complex ramifications that the food production chain has on the SDGs, on our health, and on the global burden of disease and mortality.

So, what are the new bold innovative actions in food systems that will allow us to meet the SDGs by 2030? And what are the pieces missing to get us there?

Paving the way to the food systems of the future

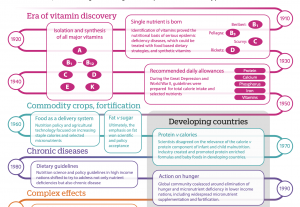

Dr. Mozaffarian remarks that “to know where we want to go, we need to understand how we got here”, so to create future solutions, we need to look at how we got to our current food system.

Our modern food system is a reflection of the legacy of the goals of the 20th century, which was shaped by two major events. First, the discovery of all the vitamins and their roles in disease development. For the first time it was discovered that a single nutrient could be the sole cause (and cure) for a disease, which of course lead into initiatives that focused of fortification. Second, the population explosion which translated into the fear of mass starvation. This is how the so-called Green Revolution came to be, prompting the mass production of starchy foods that could feed the increasing population. As a result, we have a 20th century food system that relies on heavily processed foods which are stable for transportation, which are energy-dense to fend off starvation, meaning rich in starch, fat and sugar, and which are fortified with vitamins to avoid single-nutrient diseases. In summary, food designed to ‘treat’ caloric insufficiency and vitamin deficiency.

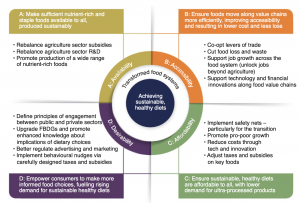

What we did not realize then, is that these ‘cures’ would lead to more serious chronic problems down the line. Chronic diseases are disabling and killing our population worldwide with conditions including diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, and many others. So now we need to switch into a food system fitted to the needs of the 21st century, focusing on nutrition equity and sustainability instead. This can be achieved through the four pillars described by Patrick Webb (who was the chair of the session on Transforming Food Systems at ASN’s Live Online 2021 Conference). First, we need to ensure that sufficient nutritious food is available to all and that it has been produced in a sustainable way. Second, we need to improve accessibility by finding ways to move along value chains in a more efficient manner, which can then result in lower costs and less food waste. Third, we need to make sure that healthier diets are affordable, lowering the demand for ultra-processed foods. And fourth, empower the consumers to make informed food choices by increasing the desirability of healthier diets.

The road ahead…

So, how can we design food systems that will meet the UN’s SDGs by 2030? What are the missing pieces? According to Dr. Mozaffarian, “we are not going to solve the problems of today with the solutions of yesterday”. So first and foremost, we need to find and create new solutions, and to do so we need to invest in science, research and innovation. We need to make huge global investments in both public and private science so that we can expand and improve every field from agriculture and food production to behavior change and everything in between. Then, we need to be able to renovate our current food environments to make them better suited for healthier diets, in particular, we need to transform those places where people buy and eat their food. We also need to emphasize the importance of diet-related chronic diseases, we need to make space to address the increasing amount of people suffering from obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and other chronic diseases that are highly linked to overnutrition.

It is also paramount to re-invent agriculture. New agricultural practices need to focus not only on the production of nutrient-rich and minimally processed foods that can be transported around the world at an effective cost, but also on new ways to mitigate the climate crisis by reducing the impact that our current practices have on the environment. If we are to reach the SDGs, we need to engage the private sector as well as the public, every stakeholder from farming to retail and hospitality industries needs a seat at the table to become part of the solution and not the problem. And lastly, we need to establish true cost accounting; so far we have only focused on how much it costs to produce food and how much it costs to buy it, but moving forward we need to account for additional costs such as healthcare costs, loss of productivity, climate and environmental costs, etc. and here is where governments can play a crucial role in designing and implementing policies that ensure that those economic tradeoffs are accounted in the market.

To be able to move onto a food system designed for the 21st century, we have to push forward the nutrition science, agricultural science and behavioral science and continue to explore emerging fields (including gut microbiome, personalized nutrition, phenolics and flavonols, food processing, additives, timing of meals or chrono-nutrition, brain health, immunity, allergies, etc.). More importantly, science has to intercept with policy, otherwise this is all stale knowledge. Dr. Mozaffarian remains optimistic that through advancing and promoting science and using science-based nutrition policies we can unite scientists, governments, and the private sector, so that we can transform our food systems to meet our current and future needs together.

Read more:

UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (https://sdgs.un.org/goals)

History of modern nutrition science—implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy. D. Mozaffarian et al. 2018, BMJ (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2392)

The urgency of food system transformation is now irrefutable. P. Webb et al. 2020 Nature Food (https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00161-0)

Transforming Food Systems: The Missing Pieces Needed to Make Them Work. E. Kennedy et al. 2021, Current Developments in Nutrition (https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa177)

New article: Can a high sugar intake predispose you to develop atherosclerosis?

Atherosclerosis is a progressive condition that starts during our childhood by accumulating fatty materials in the interior of our blood vessels. This leads to the formation of plaques that narrow the diameter of our arteries and reduces the blood flow to the organs. Atherosclerosis is one of the main underlying processes behind numerous cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction or stroke, and can be largely influenced by our lifestyle.

The way we eat, how much we exercise, and whether we smoke tobacco or drink alcohol, among others are some of the main risk factors for both atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. This means that these risk factors can be modified and therefore we can have an active role in reducing our risk for developing atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases.

However, while the effect of diet on atherosclerosis has been extensively studied, not much is known about the role that sugar consumption plays in all of this. In our latest study published on Nutrients, we explored precisely that. To do so, we studied the intake of different forms of sugar intake as well as the consumption of sugar-rich foods and sugar-sweetened beverages of over 5000 participants from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study; and we compared them to the thickness of their arterial walls measuring the Intima-Media Thickness (IMT) via ultrasound. An increase of IMT is usually the first sign of atherosclerosis, before we even develop symptoms and is therefore an important instrument for early detection and the study of prevention.

In our study, we found overall no significant associations with any of our forms to ascertain sugar intake (added sugar, free sugar, total sugar sugar-rich foods, sugar-sweetened beverages) and IMT measured at two sites (the common carotid artery and the bifurcation of the carotids). However a subtle tendency towards a thicker IMT at the common carotid artery on those participants with the highest added sugar intake could potentially point towards a higher risk of cardiovascular disease for the participants with and added sugar intake above 20% of their energy intake.

Therefore, further research is needed to confirm our suspicions by exploring the association between sugar intake and IMT in populations from different countries and age groups as well as using longitudinal studies where the progression of the disease can also be explored. Studying groups of participants with higher sugar intake could also show stronger associations between sugar intake and atherosclerosis.

Read more about sugar consumption and atherosclerosis here: González-Padilla et al. Nutrients 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051555

The snacking monster: the other villain to fight during COVID times

Just as the world keeps trying to cope with the coronavirus pandemic, another equally devastating evil has arisen, slowly creeping out of our pantries and fridges: the snacking monster! And who hasn’t been spending their semi-isolated and under socialised weekends at home idly munching their sorrows away? However, the effects that over-snacking can have on your vitamin and mineral intake and your overall health as well as on your immune system should not go unnoticed, especially in the middle of a pandemic.

It is no secret that we eat when we are bored, and lately we seem to be bored a lot more often. The coronavirus crisis has confined us in our households, deprived of outdoor entertainment and physical activity, and working from home has us now always within seconds of our overstocked fridges (a sequalae of the 2020 panic buying). So in order to save us from the dullness of lockdown we resort to food. Whether we cook it, order it, bake it or eat it directly from a bag, there is no question that food is one of the greatest stimulants that humans have right now. We all had to endure the sourdough and banana bread fever less than a year ago, but new foodie trends have emerged. Check social media if you do not believe me!

But snacking has been an issue even on pre-COVID times. Snacks, specifically the unhealthy kind, are particularly appealing when eating out of boredom. This is something that the industry takes advantage of to appeal to the consumers. A considerable amount of research goes into designing the perfect levels of saltiness, sweetness, and even crunchiness to make them as satisfying and desirable as possible. Moreover, the fact that they come in ready-made and attractive packaging it makes them almost impossible to resist.

The problem is that the over consumption of these snacks, which are considered energy-dense foods due to their high content of fat and sugar, comes hand in hand with weight-increase, unhealthier habits, and a phenomenon called micronutrient dilution. Micronutrient dilution refers to the displacement of nutrient-rich foods (high in vitamins and minerals) such as fruits and vegetables, by the consumption of energy-dense foods, which are usually low in micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

In our study, published in Nutrition & Metabolism last year, we explored the phenomenon of micronutrient dilution in relation to the intake of added sugar. Added sugars are those sugars that are not naturally occurring in foods and beverages, but that are added during the processing, manufacturing or at the table. This means that added sugar is potentially a type of sugar that could be eliminated from our diets without any collateral effects on our health status. Our study looked at the intake of nine key micronutrients in two adult Swedish samples of adults, covering a period of over two decades and compared them to their added sugar intakes. Unsurprisingly, we observed that the higher the added sugar intake, the lower the micronutrient intake. For micronutrients such as Vitamin D, selenium, or folate, this effect was particularly worrying, as up to 85% of the participants with the highest added sugar intake were not even meeting the recommendations issued by the latest Nordic Nutrition Recommendations.

A low level of micronutrient intake can not only cause disease on its own, but it is also the stepping stone to developing many other diseases and weakening our immune system. This is a particularly relevant piece of information, since nowadays we need our immune systems to be strong enough to fight the very same virus that is keeping us confined. Both the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the World Food Programme have issued guidelines recommending us to reduce the intake of foods high in sugar, fat and salt to keep our immune systems working as they should. Moreover, it has been suspected that obese people have not only up to a 33% higher risk of dying from COVID-19 but also a higher chance of developing worse symptoms that those with lower weight. So those guidelines also highlight the importance of eating a healthy overall diet and to be as active as the situation allows us in order to keep our weight within healthy limits.

So it seems quite obvious that we should not fall prey to our inner snacking monster and try to eat as healthily as possible. Perhaps, this pandemic could be an opportunity in disguise to be more mindful about the way we eat, to find healthier alternatives to the old snacks that our monsters crave and to take care of our bodies and our health, not just during COVID times, but always.

To read more about Micronutrient Dilution, you can also check the Q&A I did for BMC’s blog On health.

Eating habits in a changing society: Nordic countries

The definition of nutrition has been closely related to health and disease since its inception. However, with the development of the concept of health we have started to associate nutritional science with many disciplines and thus, we have seen the rise of crossovers between nutrition and fields such as genetics, social sciences, anthropology, psychology and behavioural sciences among others. The importance of this multidisciplinary approach to nutrition has been reflected in the very first session of the Nordic Nutrition Conference 2020, where the focus was placed on Food-related behaviours on a changing society.

Professor Lotte Holm, who teaches Sociology at the Department of Food and Resource Economics in Copenhagen University talked about the changes in eating patterns observed in the Nordics countries over a period of 12 years. Lotte pointed to the close link between meal patterns and societal structures and how our eating habits have evolved with our changing society: from pre-industrial to industrial to our current post-industrial era. Nowadays, our society is heavily marked by phenomena such as globalisation, individualism and flexible working patterns and these have all played an important role in the way we eat. Thus, our current eating patterns should reflect the adaptation to the social hypotheses and constructs of the era that we live in… or do they?

A study designed to explore everyday eating patterns in the Nordic Countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) revealed how, overall, certain trends have remained stable over time. The Nordic countries continue to have core traditional elements in their national food habits and two marked lunch cultures (hot vs cold), as well as a dominant position of meat consumption during dinners. The main meals continue to be simple in their format rather than elaborate, favouring one-course meals and foods that require little to no preparation.

However, some changes have also come about, inducing the harmonization between food cultures in the Nordic countries. These trends could point towards the increased awareness of healthier eating habits. For instance, water is becoming a more popular drink for lunch and dinners as opposed to sodas and there has been a radical decline in the consumption of cake and pastries associated with the traditional fika culture in Sweden. Also, there has been an increase in vegetarian meals and the introduction of fruits and vegetables in breakfasts and cold lunches, as well as a rise in the consumption of cereals and yoghourts for breakfast.

Another interesting discovery is the marked unwillingness of the Nordic populations to decrease their meat intake for environmental reasons. In Denmark, this was particularly remarkable as up to 70% of the participants declared that they had not reduced their meat intake nor will they be willing to do so in the future. This might come hand-in-hand, with Denmark’s strong meat production industry and suggest that public health efforts towards promoting a reduction of meat consumption need to be addressed in a more productive way.

Looking at the context in which meals occur, the study discovered that eating still mostly happens at home. Eating alone and in shorter meals (lasting less than 10 minutes) are also increasing trends in Denmark and Norway but not in Sweden. The decrease in formality of meals has opened up for the inclusion of other activities while we eat, such as watching television, listening to the radio, reading, or using electronic devices. Interestingly, a de-structuring of gender roles when it comes to meal preparation has also been observed in this study, as more men across all age groups, education levels and income have started to take charge of cooking and planning meals.

Overall, little disruption was observed in meal patterns in the Nordic countries. There was a somewhat strong tendency towards individualisation and an even stronger towards flexibilization of meal patterns, as well as an increase in convenience meals, pointing towards commercialisation but not very strongly. Conversely, these trends are much more patent in other countries such as UK where where eating does not happen in peaks but irregularly throughout the day due to different schedules and the wide availability of food at any given time of the day, what is known as ‘the grazing hypothesis’.

It seems that Nordic food cultures are becoming more and more like each other in certain aspects, although certain national differences remain, most markedly the existence of two clear lunch patterns and the adaptation to personal life arrangements. So, while Sweden and Finland tend to favour hot lunches, Denmark and Norway favour cold lunches. Also, those within the workforce tend to have longer meals with their colleagues, and those who live alone have shorter dinners in a more informal setting and usually combined with another activity, like watching television or using electronic devices. However, Nordic countries do not seem to have absorbed global patterns seen in other countries.

Looking to the future, Lotte expects to see an increase in commercial eating in the form of more meals taking place outside the household and the increase of consumption of ready-made or pre-prepared meals. However, she is also hopeful that with an increasing concern for the environment we might see an inclination to decrease meat consumption, although this seems unlikely especially in Denmark. Nutrition should no longer be considered an isolated concept and it is only through understanding the complex context that surrounds it that we can hope to influence individual choices and governmental policies that affect our eating habits with hopes of a healthier society.

For more information on the topic you can consult the book Everyday eating: in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. A comparative study of Meal Patterns 1997-2012 by Jukka Gronow and Lotte Holm (eds), Bloomsbury Academic 2019.

Revolutionising nutrition science using objective methods

Gary Frost put it nicely when he described self-reported energy assessments as the Achilles heel of nutrition science.

The difficulties with dietary assessments

During Gary Frost’s talk “Improving the accuracy of dietary intake assessment: From molecules to cameras” given at the Nordic Nutrition Conference 2020, he mentioned how many fantastic scientific breakthroughs we’ve had during the last 60-70 years, and yet, we have not figured out how to accurately assess what people eat in their day to day life.

Traditional dietary assessment methods including food questionnaire’s and dietary recalls rely on self-reported dietary data. During the 1980s, doubly-labelled water studies (an objective method determining a person’s energy expenditure) highlighted that under-reporting of energy intake was very common with self-reported diet assessment methods (1). Consequently, use of objective diet assessment methods is of interest. Using doubly-labelled water is however quite costly and may therefore not be suitable for population-wide use.

Metabolomics

As a promising method for tackling the inherent issues of self-reported diet assessment methods, Gary Frost brings up metabolomics. Specifically, analysing urine samples using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and based on the output identify a metabolic profile (with individual molecules being markers for specific foods). He presented results from a randomised controlled trial with 19 individuals, in which researchers were able to identify distinct dietary patterns based on the metabolic profiles (3). Interestingly, they were able to clearly separate individuals with ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ diets using this method. This metabolomic profiling system has also been used in free-living participants in cohorts, for example Intermap UK, where adherence to the DASH diet signified healthy eaters (3).

Further, Gary Frost presented results from a clinical trial showing how metabolomic phenotypes can be used to predict responses to dietary interventions. He highlighted two participants who responded in the same way to a diet with regard to glucose control, but that they got there using very different metabolic pathways (4). In the future, Gary Frost predicted that metabolomics will be utilised in clinical practice as well as epidemiological studies to identify metabolomic profiles and metabolic pathways as the method is relatively fast and inexpensive.

Camera technologies

Although metabolomics provide a lot of insight, it has its limitations. Certain components of the diet are currently ‘invisible’ for the metabolomic technologies, for example energy and carbohydrate intake. Along with developing metabolomics technologies, Gary Frost suggests combining it with other methods. One such method that his team is currently studying is passive dietary monitoring using imaging technologies.

The idea is to, using machine learning and artificial intelligence, identify eating episodes, food types, portion sizes, and nutritional information solely by passive (often wearable) camera monitoring. There are several ongoing studies testing these technologies in The UK, Ghana, and Kenya. So far, the results indicate that the technology provides a good estimation of weight of food when compared with direct weighing or estimations done by dieticians. However, there are many challenges, including difficulties estimating intake of shared foods and privacy concerns. There seems to be many hurdles to overcome before being able to use these passive camera technologies for diet assessment, but they could potentially evolve to become a tool to offer full nutritional insight!

References

1. Schoeller DA, Bandini LG, Dietz WH. Inaccuracies in self-reported intake identified by comparison with the doubly labelled water method. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1990;68(7):941-9.

2. Ramne S, Gray N, Hellstrand S, Brunkwall L, Enhorning S, Nilsson PM, et al. Comparing Self-Reported Sugar Intake With the Sucrose and Fructose Biomarker From Overnight Urine Samples in Relation to Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Front Nutr. 2020;7:62.

3. Garcia-Perez I, Posma JM, Gibson R, Chambers ES, Hansen TH, Vestergaard H, et al. Objective assessment of dietary patterns by use of metabolic phenotyping: a randomised, controlled, crossover trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017;5(3):184-95.

4. Garcia-Perez I, Posma JM, Chambers ES, Mathers JC, Draper J, Beckmann M, et al. Dietary metabotype modelling predicts individual responses to dietary interventions. Nature Food. 2020;1(6):355-64.

New article: Added sugar intake and cardiovascular disease risk

A new article of ours was recently published in Frontiers in Nutrition, in which we investigated the associations between intake of added sugar and sugar-sweetened foods and beverages and incident risk of stroke, coronary events, atrial fibrillation, and aortic stenosis. You can access the full article here!

Abstract

Aims: Although diet is one of the main modifiable risk factors of cardiovascular disease, few studies have investigated the association between added sugar intake and cardiovascular disease risk. This study aims to investigate the associations between intake of total added sugar, different sugar-sweetened foods and beverages, and the risks of stroke, coronary events, atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis.

Methods: The study population consists of 25,877 individuals from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study, a Swedish population-based prospective cohort. Dietary data were collected using a modified diet history method. National registers were used for outcome ascertainment.

Results: During the mean follow-up of 19.5 years, there were 2,580 stroke cases, 2,840 coronary events, 4,241 atrial fibrillation cases, and 669 aortic stenosis cases. Added sugar intakes above 20 energy percentage were associated with increased risk of coronary events compared to the lowest intake category (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.09–1.78), and increased stroke risk compared to intakes between 7.5 and 10 energy percentage (HR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.03 and 1.66). Subjects in the lowest intake group for added sugar had the highest risk of atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis. More than 8 servings/week of sugar-sweetened beverages were associated with increased stroke risk, while ≤2 servings/week of treats were associated with the highest risks of stroke, coronary events and atrial fibrillation.

Conclusion: The results indicate that the associations between different added sugar sources and cardiovascular diseases vary. These findings emphasize the complexity of the studied associations and the importance of considering different added sugar sources when investigating health outcomes.

Prevention of type 2 diabetes is not only plausible, it is highly achievable

During the Prevention of type 2 diabetes session at the Nordic Nutrition Conference 2020 (14-16 December), it was made clear that prevention of type 2 diabetes is highly achievable, as has been proven in some important studies over the past decades. Below follows a summary of a few of those studies.

Finnish DPS study

The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) was among the first diabetes prevention trials ever made (1). In the study, 523 individuals with impaired glucose tolerance were recruited between 1993-1998. Individuals were randomized to a lifestyle intervention group or a control group. Study participants had seven sessions with a nutritionist during the first year, and four per year for the remaining of the study. The lifestyle intervention was constituted by the following goals and advice:

- Weight reduction: 5% or more

- Fat intake <30E%

- Saturated fat intake <10E%

- Fiber ≥ 15 g per 1000 kcal

- Exercise: moderate ≥ 30 min/day

The incidence of diabetes was 58% lower in the intervention group than in the control group after an average 3.2 years (1). These results are in line with those of the three other diabetes prevention trials from the same era:

- US Diabetes Prevention Program (n=3234 recruited 1991-1996) could see that incidence was reduced by 58% with the lifestyle intervention and 31% with the metformin intervention compared to the control group after an average of 2.8 years (2).

- Da Qing Diabetes Study (n=577 recruited 1986) could see decreased incidence in type 2 diabetes in the diet group, physical activity group and the diet+physical activity group (36-53%) compared to control after 6 years (3).

- Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme, (n=531 recruited 2001-2002) showed that lifestyle management and metformin treatment reduced the type 2 diabetes equally (ca 28%) compared to control after 3 years (4).

From these studies, it became evident that type 2 diabetes can be prevented with lifestyle modifications.

DIRECT study

The DIRECT (Diabetes Remission Clinical Trail) study had their focus on reversing newly diagnosed diabetic patients rather than on diabetes prevention. Their objective was based on that other studies have indicated that a 15 kg weight loss could normalise life expectancy in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

In the DIRECT study, 298 patients who have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes maximum 6 years ago were taken out of their medications and instead started a 3 months low calorie diet with total diet replacement. After three months, participants were gradually reintroduced to solid foods for two months and after that followed 24 months of weight maintenance. All of this was performed within the primary health care setting.

After 1 year, 46% in the intervention group had achieved remission (5), and at 2 years, 36% were in remission (6). In line with this were a wide range of other health markers improved in the intervention group, and the magnitude of improvements was related to the amount of weight lost and maintained.

This study indicates how plausible type 2 diabetes remission actually is within the primary health care, as long as we have enough resources to focus on this issue. Most excitingly is that this is currently being implemented within the primary health care in the UK.

PREVIEW study

The PREVIEW (PREventing Diabetes through Interventions in Europe and the World) is a multi-center randomized controlled trial where individuals with prediabetes were included (7). The interventions started with a two months weight loss phase using a low-calorie diet (as in DIRECT). After that, the goal was to compare to different dietary regimens for weight loss maintenance for 34 months; one considered a standard diabetes preventing diet and another with higher protein content and lower glycaemic index (GI) based on the successful results from the DiOGenes study (8). So, a high protein-low GI diet was compared to a moderate protein-medium GI diet and both of these diets were paired with either a high or moderate intensive physical activity scheme, resulting in four different intervention arms.

The study started in 2013 and was finished in 2018, and the main results were recently published (7). A total of 2326 individuals were recruited to the study, but to continue to the weight maintenance phase, a minimum of 8% weight loss was necessary. This was achieved by 80% of the participants (n=1857). Among these, 3,1% developed type 2 diabetes during the three year long study. This was much lower than expected, indicating that the interventions were effective in reducing the type 2 diabetes incidence. Further, there was no difference in incidence between the different intervention groups. Weight loss and various measures of glucose homeostasis were also the same in all groups, with the exception for normoglycemia that was significantly less achieved in the high protein-low GI diet with high intensity training. But why this is, is difficult to explain.

So overall, both dietary regimes were effective in reducing type 2 diabetes risk, and the incidence were much lower than expected. However, of major concern are indications of a limited adherence to the interventions, especially to the high protein intake, and a rather high drop-out rate, 26% year 1 and 41 % year 3, equally distributed between intervention groups.

Conclusion

All three presentations during this session of the Nordic Nutrition Conference 2020 indicated how the ability to prevent or revert type 2 diabetes using diet and lifestyle interventions is constantly higher than we expect. The successful actions for tackling type 2 diabetes, in for example primary health care, have now been shown time after time. So, one can certainly wonder why more is not implemented? Why isn’t more done when we know of many alternative ways in how to prevent type 2 diabetes? And luckily, the research indicates that it is not the details that are important (for example whether protein intake is 15 or 25E%), it’s about getting enough encouraging visits and phone calls to keep the intervention going. We don’t need difficult expert dietary advice, we need simple weight loss advice for healthy living, but we need them often and with engagement from the health care.

- Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. The New England journal of medicine 2001;344(18):1343-50. doi: 10.1056/nejm200105033441801.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England journal of medicine 2002;346(6):393-403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

- Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, Hu ZX, Lin J, Xiao JZ, Cao HB, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes care 1997;20(4):537-44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537.

- Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V, Indian Diabetes Prevention P. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia 2006;49(2):289-97. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0097-z.

- Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, Peters C, Zhyzhneuskaya S, Al-Mrabeh A, Hollingsworth KG, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet 2018;391(10120):541-51. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33102-1.

- Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, Peters C, Zhyzhneuskaya S, Al-Mrabeh A, Hollingsworth KG, et al. Durability of a primary care-led weight-management intervention for remission of type 2 diabetes: 2-year results of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2019;7(5):344-55. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(19)30068-3.

- Raben A, Vestentoft PS, Brand-Miller J, Jalo E, Drummen M, Simpson L, Martinez JA, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Stratton G, Huttunen-Lenz M, et al. The PREVIEW intervention study: Results from a 3-year randomized 2 x 2 factorial multinational trial investigating the role of protein, glycaemic index and physical activity for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020. doi: 10.1111/dom.14219.

- Larsen TM, Dalskov SM, van Baak M, Jebb SA, Papadaki A, Pfeiffer AF, Martinez JA, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Kunešová M, Pihlsgård M, et al. Diets with high or low protein content and glycemic index for weight-loss maintenance. The New England journal of medicine 2010;363(22):2102-13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007137.

Curious about sugar intake?

Would you like to learn more about sugar intake? Do you want to know how it can be associated with risk markers or genetic factors? Are you curious about how policies regarding sugar intake are reflected in the media?

Join in for my halfway review and learn more about my PhD project!

The seminar will be held on Zoom next 24th November 2020 starting at 10:00 (CEST)!

Don’t miss out the opportunity, these things don’t usually happen online!

Comments