It is widespread knowledge that a diet with better carbohydrate quality is beneficial for our health. But what does this actually mean? This was recently discussed during a so-called Sponsored Satellite Program at the American Society for Nutrition’s conference Nutrition 2020 Live Online. The session was named Importance of Carbohydrate Quality and was sponsored by Nestlé Research and Development. Since I (Stina Ramne speaking), now have spent almost 3 years completely focused on the health effects of a high added sugar intake during the progression of my PhD, I will not only summarize what the four speakers brought forward during this conference session, but also give at little bit of my personal view of it.

The first speaker was Luc Tappy, University of Lausanne, who gave an informative and brief introduction to what carbohydrates are and how they are divided into sugars, starches and fibers.

He also brings forward a very interesting perspective of how to look at carbohydrate quality. A perspective which I have never heard of before and which also appears somewhat ancient and not really up to date with today’s nutritional needs and challenges (I’ll come back to why this is). Tappy claims that quality (independent of what is referred to) is defined as “meeting the customers needs, while being absent of adverse effects”. Since carbohydrates is not an essential nutrient in any way, the need and role that carbohydrates have is simply to provide energy. So a carbohydrate of good quality in this sense, is a carbohydrate that efficiently provides energy, while have no adverse effects. Tappy very neatly shows how those parameters seldom go hand in hand and that it is often the case that carbohydrates or carbohydrates-rich foods often fulfils one, but lacks the other of these qualities. For example, he ranks sugar-sweetened beverages as the most efficient energy-providing carbohydrate-rich food, but also the food with the strongest evidence for adverse effects. Whole fruit and whole grains provide energy less efficiently, but lack adverse effects. When comparing starch, sucrose and fructose, it gets a bit more nuanced. Fructose is first of all not perfectly absorbed, and secondly, it’s partly metabolized to lipids instead of glucose, hence it does not provide energy as efficiently as starch, which generally is perfectly degraded to glucose and used as energy. Fructose is also the saccharide with the strongest evidence for adverse health effects. In summary, with the carbohydrate quality definition provided by Tappy, fructose is clearly a shit-food, starch is quite OK, and sucrose falls in the middle (probably because it’s also a combination of fructose and glucose in its molecular composition).

What did remain unaddressed in Tappy’s presentation, which I consider is an important point, is the reason why the parameters of “efficiently provide energy” and “absence of adverse effects” don’t go hand in hand. This is simply because today’s society’s most profound nutrition challenge is that we have too much energy available, resulting in weight gain, obesity and all the diseases following that. The so-called adverse effects are caused by to efficient energy allocation. The big hole in Tappy’s reasoning is the claim that the need we have from carbohydrates is to efficiently provide energy, which simply is not true in most of today’s high- and middle-income societies. Previously, it is true this has been a need that we had from carbohydrates, such as before the agricultural and industrial revolutions when food supplies were scarce. Also, as recently as during the first half of the 20th century, a time defined by wars, this was true. Now, on the other hand, the need we have from carbohydrates are different. What we actually need from carbohydrates is in my opinion somethings else.

- Fibers!

- Vitamins, minerals and polyphenols such as in fruit, vegetables and whole grains

- “Fillers” that provide long-lasting satiety

- Alternative parts to our diet so it’s not solely constituted by pure fats and environmentally detrimental animal foods and low-energy high-water-demanding vegetables (that generally are low in carbohydrates)

The second speaker was John Sievenpiper, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto, who concluded the evidence summarized in meta-analyses of the health effects of carbohydrate quality based on 3 different domains on how to define good carbohydrate quality.

An interesting side note is that Sievenpiper started his presentation by very clearly going through a large slide with all his disclosures, but apparently he forgot the one he has had with Coca Cola. Well well, back to three domains of carbohydrate quality and its’ relations to cardiometabolic health.

- Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL)

- Both high GI and GL are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease from the summarized prospective cohort evidence, and the effect is larger from GL compared to GI. From intervention trial evidence, low GI improve glycemic control and cardiometabolic risk factors in diabetes.

- Dietary fiber

- From epidemiolocal evidence, dietary fiber is associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. From RCTs, high fiber diets, especially high viscous soluble fiber, improve systolic blood pressure and glycemic control in diabetics.

- Food-based approach

- Whole grains are associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease and RCTS of oats and barley have shown improved LDL-cholesterol and systolic blood pressure, and improved glycaemic control in diabetics.

- Pulses are associated with reduced incidence in coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease and hypertension from epidemiological evidence. RCTs of diets high in pulses have in summary shown reduced glycemic control, LDL cholesterol, body weight and systolic blood pressure.

- Fruits are associated with reduced diabetes incidence and reduced cardiovascular- and all-cause mortality as seen in prospective cohorts. High fruit intake also reduced LDL-cholesterol as systolic blood pressure as evidenced from RCTs.

So if you weren’t convinced just yet how important it is get your carbohydrates from good quality sources, the Global Burden of Disease project have concluded that among all risk factors contributing to disability-adjusted-life-years in North America, low intake of whole grains made it into the top 10 list.

Last in the session followed two presentations by Flavia Fayet-Moore, Nutrition Research Australia, and Dariush Mozaffarian, Freidman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, that were so connected that I will discuss the two presentations jointly.

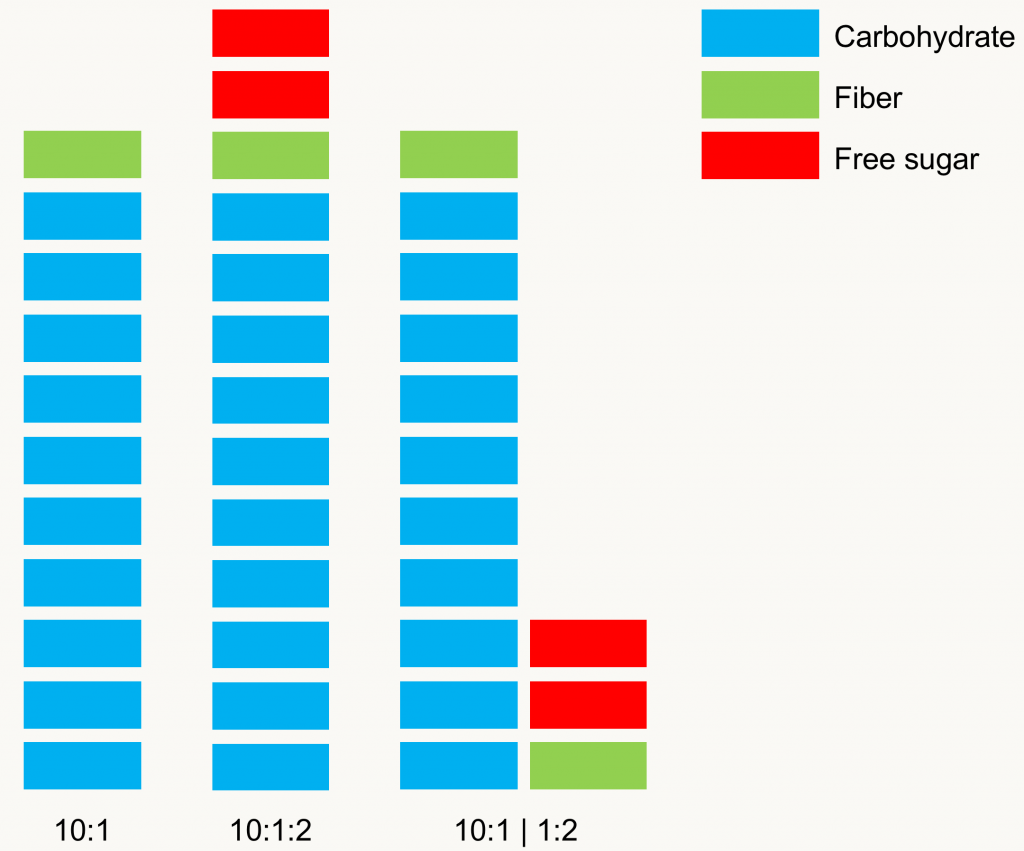

Dariush Mozaffarian’s research team have just published a new article in PLoS One suggesting and elaborating a new metric on how to measure carbohydrate quality. A refreshing addition to the classsic GI and GL metrics. The inspiration from this new metric came from the American Heart Association, which in 2010 suggested a total carbohydrate-to-fiber-ratio of >10g carb per 1g fiber, i.e. 10:1, to assess foods with unbeneficial carbohydrate quality, i.e. foods to limit intake of. Foods with a ratio between 10-5:1, on the other hand, were considered a good choice and foods with a ratio of <5:1 were an excellent choice (however, very few options exist).

Mozaffarian with colleagues have now evaluated this ratio, as well as made alternatives to it which also incorporate the free sugar content of the foods. This is important since many foods that are high in fiber and appear healthy, can at the same time be high in sugars, such as granola and dark bread. Favet-Moore and colleagues have also evaluated these carbohydrate quality metrics in an Australian population. She emphasizes the importance of validating different metrics in different populations, since food habits, preferences and options differs between different food cultures, even among food cultures that from a distance appears quite similar, such as American compared to Australian.

So what are these carbohydrate quality metrics and how do they relate to diet quality?

10:1:2 = 10 g carbohydrate: ≥1 g fiber: ≤2 g free sugars

10:1|1:2 = 10 g carbohydrate: ≥1 g fiber & ≥1 g fiber: ≤2 g free sugars

All these different metrics associated with a diet containing less calories, total fat and saturated fat, while more fiber, protein, potassium and magnesium in an American setting. In the Australian setting, all ratios associated with higher diet quality and higher nutrient intake. The 10:1 ratio was achieved by 50% of adults, the 10:1:2 was achieved by 33% of adults and the 10:1|1:2was achieved by 41% of adults.

“Overall, 10:1 and 10:1|1:2 identify the largest nutritional improvement and the broadest product options” Mozaffarian

In my own opinion, this way of looking at carbohydrate quality appears very appealing, while still super simple. How come I haven’t thought of it? Kudos to everyone involved in this work!

Before we reach the end I just want to share some more thoughts. What I think this carbohydrate quality session lacked was a discussion about the finetuning in the lower end of the carbohydrate quality spectra, where we find sugars and sugar-rich foods and beverages. These foods and nutrients are too often lumped up into one and their potential health effects are generally not differentiated between them. In the same way as how fiber, whole grains, pulses, low GI-diet, etc were differentiated when summarizing their health effects by Sievenpiper, we must differentiate between sugar-sweetened beverages, total intake of added sugars and other sources of added sugar. I think it’s an issue that research findings on sugar-sweetened beverages so often are extrapolated to apply to total intake of added sugars when studies time after time fail to find convincing evidence about the risks of a high sugar intake in general, in contrast to the studies made on sugar-sweetened beverage intake.

If I would bring this all together into a simple message. Eating good quality carbohydrates is beneficial for health, independently of how you define carbohydrate quality. The foundation always lies in finding a balance between fibers and sugars. Or actually an imbalance, where fibers outweigh the sugars.